Cambodia travel corridor: architectural time travel is on offer in the capital Phnom Penh

Cambodia has been put on the travel corridor list, and its absorbing capital, where New Khmer meets Art Deco, merits a visit before heading to the beaches

Somerset Maugham, English novelist and lifelong Francophile, visited Cambodia in 1922, remarking, “The French carry France to their colonies just as the English carry England to theirs.” He described the capital, Phnom Penh, as having, “broad streets with arcades in which are Chinese shops, formal gardens and facing the river a quay neatly planted with trees like the quay in a French riverside town.”

Following independence in 1953 the enduring orientalist image was soon interrupted. “In 1975 we started to have Khmer Rouge,” described Sokagna, a graduate in Architecture from Phnom Penh’s Royal University of Fine Art. “They moved people out of the city, to the provinces to work in the rice fields. It was very hard. Not enough food. Most people died – around two million. They killed all intelligentsia, all managers. I lost my grandfather.”

Contemporary reports described the city as abandoned. After Vietnamese troops captured Phnom Penh on 7 January 1979, people returned to the city and found buildings empty, their owners and their families “smashed” in the regime’s nihilistic race to Year Zero. In need of shelter, many simply squatted, repurposing apartments and municipal structures as homes. A law passed in 1993 gave legal title to these new residents, conferring complex fractional ownership on much of Phnom Penh’s colonial buildings.

In the city’s French Quarter today the bright yellow Neo-Classical landmark of the Post Office has weathered the storm. Steps lead inside to where modern counters still serve the public and wooden PO Boxes line the wall. Iterative remodelling since Daniel Fabra’s original 1890 build has kept the structure relevant. “In front was a garden square,” said Sokagna surveying the view, as we walked through the city in February. “Now it has changed to a parking lot.”

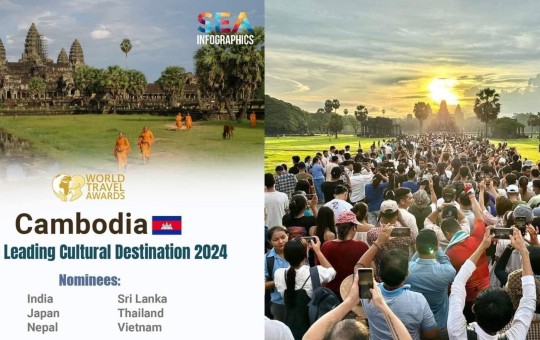

Pre-pandemic, though some travellers visited Phnom Penh, the majority bypassed the city, flying directly into Siem Reap and exploring the remarkable nearby Angkor temple complex. Though sprawling and at times unkempt, the capital deserves at least a few days’ exploration.

Faded relics and modern additions

Across the road, the faded pastel of Le Grand Hôtel, at one time the best address in town, has progressed beyond shabby chic to sorry state. Obscured by ramshackle additions, the hotel still seemed a busy focus. Sokagna led the way, dodging tuk-tuks and motorcycles, entering the building under a balustraded archway. Climbing a winding staircase, it was clear there were no paying guests.

Though some room numbers remain visible, unlit accommodation now serves as homes. In one room a man sat on the floor preparing vegetables, while coconuts lay piled against the wall. At the end of the corridor a woman pulled a thin curtain across a doorway. The sounds of chatter, competing televisions, radios and of domesticity drifted through the building. “It’s mixed owners,” said Sokagna. “If all owners agree it will be sold and knocked down. But if one says ‘No’ they cannot.”

Emerging into daylight, one of Phnom Penh’s newest structures dominated the skyline. The 187-metre Vattanac Capital building dwarfs its surroundings, containing a complex of high rolling European designer stores, the city’s most prestigious office space, and the five-star Rosewood hotel whose sci-fi fantasy Sora skybar cantilevers out from the 37th floor.

Saying goodbye to Sokagna, I hailed a tuk-tuk before asking a final question about the future. “Chinese developers come. They always demolish old buildings”, she said. “We do not have a policy for heritage buildings.”

Sclerotic traffic made the short ride to Phsar Thom Thmey, Central Market a long journey, but it was worth it. A remarkable piece of urban Art Deco designed by Jean Desbois and completed in 1937, Phsar Thom Thmey was once Asia’s largest covered market. The purity of its exterior is mitigated by encroachment of surrounding stalls. However, having penetrated a perimeter of T-shirt and tatt shops, inside soaring ceilings, clean sightlines and wealth of natural light all shout a modernity that belies the building’s age.

In contrast, south of the centre, there’s no coherent aesthetic to the chaotic crush and dark passageways of Psah Toul Tompoung, or Russian Market. Named for its appeal to canny 1980s Soviet shoppers, the aggregation of tin-roofed wooden shacks occupies a square in the southern French Quarter. Its intense offering extends from exotic fresh produce, street food and fabric to electronics and glow-in-the-dark Buddhas.

An evening stroll and sundowner

From early evening, a walk along the Tongle Sap Riverside approximated to a southeast Asian passeggiata. Heading north from the Royal Palace to Wat Phnom, the wide Riverside path was punctuated by middle-aged formations exercising to pumping music, strolling families, and couples, all enjoying cooler evening air. Just off the path, Juniper’s open-air bar on the 12th floor of The Point Hotel offered sundowner views along the Tonle Sap towards the Cambodia Japan and Cambodia China Friendship Bridges. A pandan-flavoured gin and tonic enhanced an unfolding evening.

Covid success – through strict measures

In the nine months since my visit, Cambodia has fared much better during the Covid crises than most, to date recording no mortalities and with infections in the low hundreds. Earlier this month, Hungary’s foreign minister tested positive after visiting Cambodia, prompting Prime Minister Hun Sen to go into quarantine along with several of his staff. Schools, clubs and cinemas were closed in Phnom Penh for two weeks. The swift action is indicative of a strict policy that appears to be keeping infection numbers low. Tourists are now permitted back in the country, but must obtain a negative Covid test result 72 hours before travelling to Cambodia, prove that their medical insurance includes a minimum of $50,000 for medical cover and deposit $2,000 on arrival for Covid testing and to cover potential related costs.

Otherwise, hand sanitising and mask wearing is now ubiquitous but otherwise life has not shifted to a “new normal”. In Phnom Penh, the city’s melange of southeast Asian motifs, ornate Beaux-Arts, Neo-Classical, Art Deco and mid-century New Khmer architecture may be diminished, but unlike much Cambodian contemporary history it has not been erased. Having endured the Khmer Rouge, today’s battles for the city’s identity involve ruthless ideologues of steel and glass development, often funded by Chinese investment, sees pockets of heritage buildings – from temples and palaces to colonial relics – surrounded and losing ground. Whatever the future holds for Phnom Penh, this time the invading army will not save the day.

By: inews.co.uk